As regular visitors to these pages know, the recent addition of the small schooner Sara B to our “fleet” has fanned the flames of a long standing interest in local maritime history. Lake Ontario has plenty of it. Some has been well documented by the capable historian/sailors Robert Townsend (see Bobs Nautical link on our home page) and C.H.J. Snider who owned a sailed a working schooner on the lake and from whose books most of this comes.

The first sailing vessel on all the Great Lakes was the short lived Frontenac, launched in 1687 on Lake Ontario to ferry supplies for the building of the better known Griffin above Niagara Falls. The last working cargo schooner on the Great Lakes was the two master Lyman Davis, burned near Toronto in 1934. She was the vessel that Guy Hance sailed aboard as a teenager as detailed in the waterfront tales entry on the waterfront log on line. (The Kruse family’s two master the Eugie aka the Museum Ship) made it to 1936 I’m told, but she was built on the Chesapeake and mostly motored around the lake in her Museum ship mode).

In between those dates thousands of schooners some as small as our own twelve ton Sara B, some three hundred ton or more worked upon Lake Ontario. The bigger 3 and 4 masters usually traded on the upper lakes and the size of vessels bringing lumber and western wheat to Lake Ontario ports was limited by the Welland canal’s depth ( nine feet) and lock sizes. Oswego launched many schooners in the 19th century as did Picton, St. Catherines and a dozen other Canadian ports.

The “golden age of sail” for them was in the 1840s and 50s as then they had little competition for freight from wood burning steamers. During that time the freights of grain and lumber and general produce and merchandise were highly profitable. Even in the early 1870s Snider records the Antelope made 6000 dollars carrying a cargo of grain from Chicago to Kingston. She cost $18,000 to build. In good times a schooner could pay for its building in a single season.

After the Civil War the age of sail on Lake Ontario began a slow prolonged decline. The expanding network of rail lines and the increasing efficiency of steamers made it harder to compete. Steamboats now had compound engines and increasingly sued screw propellers and steel hulls. They were easier and faster to load bulk coal in. Trains could run year around.

Still the schooners hung on, through the 80s and 90s. One of the last profitable freights for them was Canadian barely carried to Oswego malt houses. A tax on whiskey after the Civil War gave upstate breweries a boost. At one point in the 1890s a third of all Canadian barley exports came to Oswego. Then the McKinley tariff killed it off.

Still the schooners sailed on carrying lumber, shingles, fence posts and coal until well into the 20th century. World War I gave them a brief reprieve as it stimulated demand for coal. But old age speedily thinned their ranks after that. By the 1920s a call by one at the Fair Haven trestle was a rare event. Here’s a few photos of old timers from the Sterling Historical Society’s archives.

The Julia Merrill was one of the last schooners to visit Fair Haven’s trestle regularly- she made it into the 20s. Note the yard cockbilled to allow for loading below shows the same vessel towing in behind the railroad tug possibly around mid 1920s.

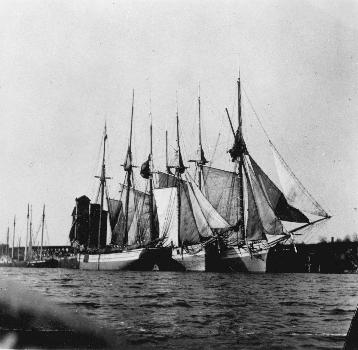

These

rafted up schooners are apparently drying sails in Fair Haven.

Judging from their waterlines, they are waiting to load. Other photos

show the trestle as very busy so I wonder if this might be World War

I times. The dark shape in background is the grain elevator now long

gone.

These

rafted up schooners are apparently drying sails in Fair Haven.

Judging from their waterlines, they are waiting to load. Other photos

show the trestle as very busy so I wonder if this might be World War

I times. The dark shape in background is the grain elevator now long

gone.

The caption says this is Will Grant’s Gazelle, perhaps around 1910. She’s on the east side of Fair Haven Bay, apparently coming into the dock under sail single handed. Perhaps her owner is back there aft? Sant says she was around 30 tons and may have been involved in some cross lake trade. Sant also says she got ashore under Sitts bluff once but was successfully pulled off. According to Lorne Joyce, a Canadian historian, this vessel was built on Great Sodus Bay and was later employed by Claude Cole at Main Duck Island for freighting where after a long useful life, she quietly settled her bones to the bottom in the 1930s.